World News

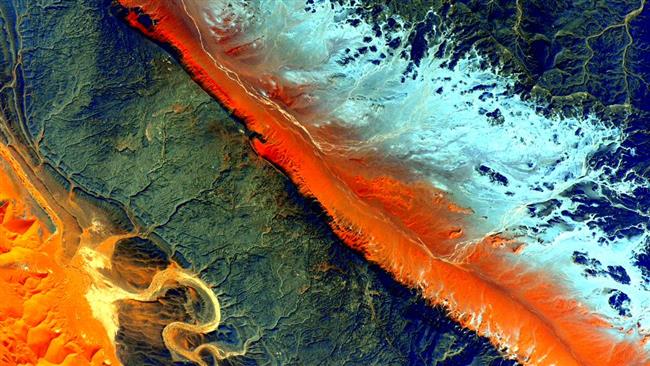

Feast your eyes on space-taken pictures of Sahara

Hot, barren and parched on the surface, the Sahara appears stunning in beauty and painted in glowing colors from space, when looked from astronaut Scott Kelly’s camera.

On a year-long mission in the International Space Station, the 51-year-old American astronaut has recently posted on his twitter the following jaw-dropping high-quality images of the great North African desert, taken from an altitude of 400 kilometers (250 miles).